Therapeutic Focus

Depression

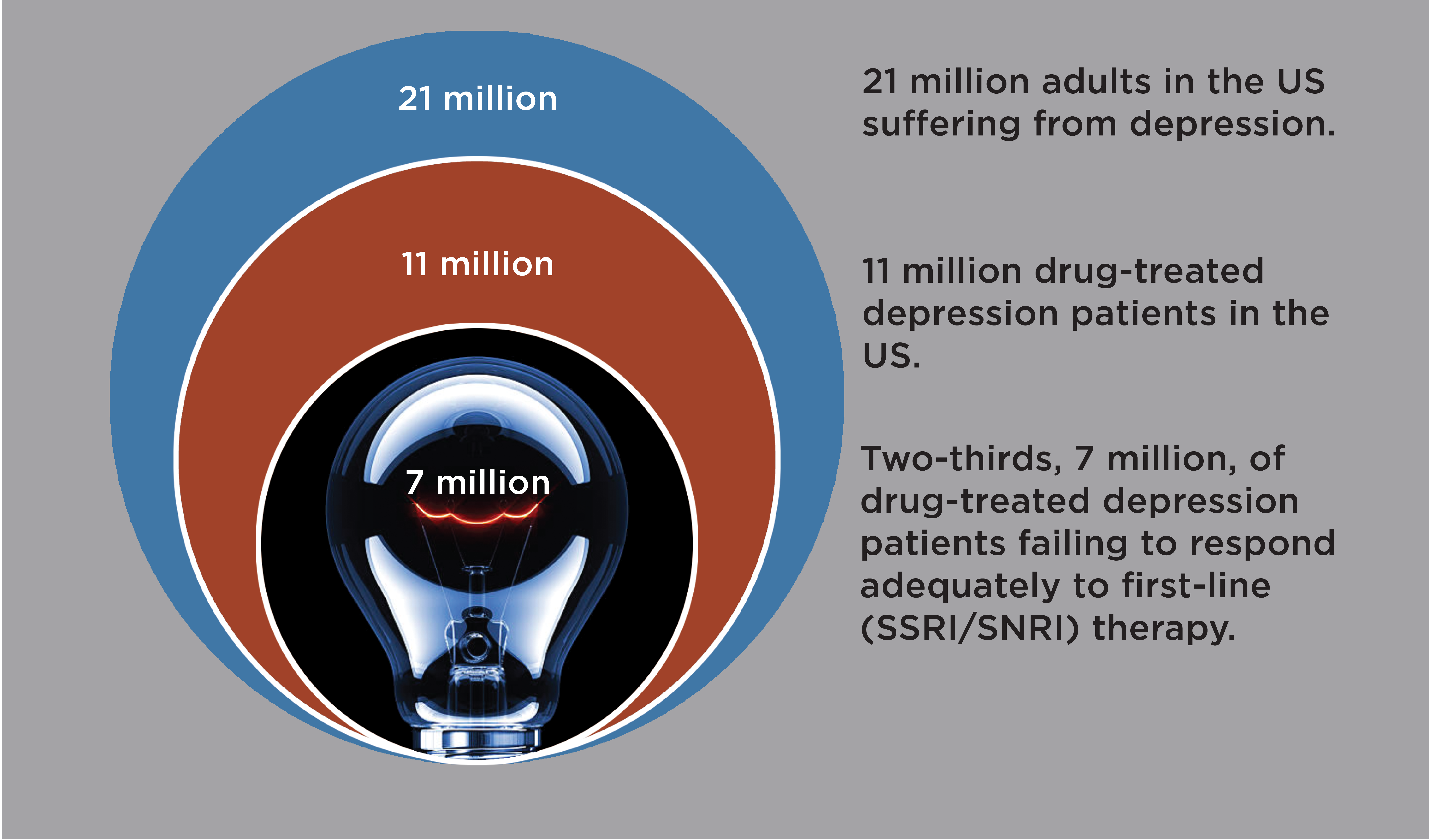

Globally, 400 million adults suffer from depression(1), with 21 million adult depression patients alone in the US. Twice as many women as men are diagnosed with depression(2). Depression impairs all aspects of life, from vocational and scholastic performance to social and familial relationships(3, 4). Depression is associated with increased risk of diabetes, obesity, cancer, and cardiovascular disease, and with reduced life span(5).

Depression diagnosis

Depression is diagnosed when a person experiences depressed mood and/or loss of interest or pleasure in daily activities for at least 2 weeks and has additional specified symptoms such as problems with sleep, eating, energy, concentration, or self-worth.

First-line antidepressants have limited efficacy and self-limiting pharmacology

First-line antidepressants (e.g. Prozac®, Paxil®, Cymbalta®) treat depression by blocking serotonin transporters in the brain. Blocking serotonin transporters relieves a brake on serotonin activity. However, serotonin transporter levels are extremely low in the human neocortex(6, 7), only a few percent of levels in the rodent cortex(8). Consequently, in the human brain first-line antidepressants only elevate active serotonin—i.e. extracellular serotonin—modestly, inconsistently, and with a delay(9, 10), and treat depression only modestly, inconsistently, and with delay(11). While some patients respond well, fully two-thirds of patients respond inadequately to first-line antidepressants(11). Increasing dose has no or modest added efficacy, as first-line antidepressants block most serotonin transporters already at standard doses(12). Switching to a different first-line antidepressant or an atypical antidepressant (e.g. Wellbutrin®) enhances efficacy in only a fraction of patients(13). For newer branded antidepressants, e.g., Trintellix® and Auvelity®, there are little evidence for meaningful mechanistic differentiation or therapeutic advantages over generic first-line antidepressants(14-16).

Next-line antidepressants – Limited added efficacy and safety concerns

Atypical antipsychotics (e.g., Abilify®) is the only oral drug class proven and FDA-approved to treat depression responding inadequately to first-line antidepressants(17). Atypical antipsychotics are administrated adjunctively (as add-on) to augment first-line antidepressant therapy. But atypical antipsychotics works well in only 1 in 9 patients(18) and carry safety concerns, e.g., metabolic anomalies and tardive dyskinesias(19).

The urgent need for new outpatient next-line antidepressants

Promising new antidepressant therapies have been FDA-approved, such as brain stimulation and Spravato® (intranasal esketamine), or are in development, notably psychedelics.

While life-saving for some patients, such therapies are difficult to implement at scale, due to in-clinic administration, high staff requirement, dedicated rooms, close follow ups, and consequent high cost and low access(20).

In the US, there is a dire shortage of mental health facilities and workers(21). Securing a brief psychiatric appointment can be a challenge. Two thirds of mental health patients never see a mental health care professional(22).

To make a true impact on depression therapy—at scale, for the majority of depression patients for whom expensive in-clinic therapies are out of reach—new next-line antidepressants are urgently needed, (i) with proven efficacy beyond first-line antidepressants, (ii) good safety, (iii) no abuse potential, and (iv) convenient at-home administration.

New antidepressant candidates should be based in clinical evidence. All (100%) FDA-approved psychiatric drugs are based in primary clinical evidence. Animal behavioral models have thus far failed to predict therapeutic efficacy of novel psychiatric drug candidates in humans(23, 24).

EVX-101 – A novel scalable next-line antidepressant

Administered adjunctively, EVX-101 amplifies extracellular serotonin—and hence brain serotonin activity—beyond the effect of a first-line antidepressant, which dozens of clinical depression studies support augment antidepressant efficacy(25-29). EVX-101 would be safe, have no abuse potential, have therapeutic potential across mood disorders, and as a tablet be easy to prescribe and administer at home. Thus, EVX-101 could make a large positive impact on depression and mood disorder therapy.

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

In the US, 4 million adults suffer from OCD, with thrice as many women as men diagnosed(30). OCD is often long-lasting and disabling. Half of OCD patients suffer severe impairment(31). OCD carries high health care and overall societal economic cost(32).

OCD diagnosis

OCD is defined by uncontrollable and recurring thoughts (obsessions), repetitive behaviors (compulsions), or both, causing significant distress and interfering with everyday life(31). Common obsessions and compulsions include concerns about contamination coupled with washing and concerns about symmetry coupled with ordering or counting(33).

Serotonin treats OCD symptoms

The mainstay of OCD therapy is first-line antidepressants, i.e., selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors as such Prozac® and Paxil®, FDA-approved in the 1990s. Since then, no new drugs have been approved for OCD. Many OCD patients experience meaningful relief from first-line antidepressants. But only few achieves remission. Most continue to experience disabling symptoms(34). Unfortunately, there are no next-line drugs approved for OCD. Adjunctive therapy with atypical antipsychotics may modestly augment efficacy but are not approved for OCD and carry safety concerns(34). Brain stimulation is effective and approved for OCD but is difficult to scale due to high resource requirements.

Interestingly, doubling or tripling first-line antidepressant dose in OCD, compared to usual doses used in depression, provides modest, but measurable, additional symptom relief(34). The additional elevation in extracellular serotonin (serotonin activity) from such high doses would be modest, as usual doses block almost all brain serotonin transporters(12). Further, pilot reports find adjunctive 5-HTP (serotonin precursor) or tryptophan (precursor to 5-HTP) to augment first-line antidepressant efficacy in OCD(35-37). Thus, augmenting brain serotonin elevation beyond the effect achievable with first-line antidepressants could treat more OCD patients better.

EVX-101 could be the first approved oral next-line OCD therapy

Adjunctive EVX-101 could treat OCD patients responding inadequately to first-line antidepressants, by potently and dynamically amplify brain extracellular serotonin beyond the first next-line antidepressant effect. EVX-101 could become the first FDA-approved next-line OCD drug therapy, addressing one of the largest and most intractable unmet needs in Psychiatry today.

Suicidal Ideation

In 2022, almost 50,000 died by suicide in the US, an all-time high, and more than 1.7 million people attempted suicide(38). Among young people, suicide is the second leading cause of death. Veterans have a 70% increased risk of suicide compared to non-veterans(39). Suicide has risen to epidemic levels and is a national emergency in the US. More than 12.5 million seriously considers suicide in the US every year. Every year 1 million are hospitalized for acute suicidal ideation crisis(38).

In 2022, almost 50,000 died by suicide in the US, an all-time high, and more than 1.7 million people attempted suicide(38). Among young people, suicide is the second leading cause of death. Veterans have a 70% increased risk of suicide compared to non-veterans(39). Suicide has risen to epidemic levels and is a national emergency in the US. More than 12.5 million seriously considers suicide in the US every year. Every year 1 million are hospitalized for acute suicidal ideation crisis(38).

Living under the cloud of suicidal ideation—even if never realized as a suicide attempt or completed suicide—is a life of torment and misery, and represents a critical unmet need in its own right(40).

Unfortunately, there are no FDA-approved drugs for suicidal ideation, suicidal ideation crisis, or to prevent future suicides – albeit IV ketamine may have efficacy(41). As for all Psychiatric drug discovery, the quest for drugs for suicidal ideation are hampered by the lack of animal models. We rely on clinical evidence to inform suicidal ideation drug discovery.

EVX-301 could be the first FDA-approved drug to treat suicidal ideation crisis

Evecxia Therapeutics is developing EVX-301 to treat patients hospitalized for acute suicidal ideation crisis. EVX-301 is designed to amplify brain serotonin with fast onset, which convergent clinical evidence suggest could treat suicidal ideation with fast onset(42-46).

References & Abbreviations

- WHO (2023): Link

- NIMH (2021).

- Lerner D, et al. (2010): Am J Health Promot. 24:205-213.

- Frojd SA, et al. (2008): J Adolesc. 31:485-498.

- Steensma C, et al. (2016): Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 36:205-213.

- Varnas K, et al. (2004): Hum Brain Mapp. 22:246-260.

- Hansen JY, et al. (2022): Nature neuroscience. 25:1569-1581.

- Mirza NR, et al. (2007): Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 31:858-866.

- Nord M, et al. (2013): Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 16:1577-1586.

- Haahr ME, et al. (2014): Mol Psychiatry. 19:427-432.

- Trivedi MH, et al. (2006): Am J Psychiatry. 163:28-40.

- Sorensen A, et al. (2022): Mol Psychiatry. 27:192-201.

- Papakostas GI, et al. (2008): Biological psychiatry. 63:699-704.

- Zhang J, et al. (2015): J Clin Psychiatry. 76:8-14.

- Werling LL, et al. (2007): Experimental neurology. 207:248-257.

- Axsome (2020): STRIDE-1 Phase 3 Trial of AXS-05 in TRD.

- Berman RM, et al. (2007): J Clin Psychiatry. 68:843-853.

- Spielmans GI, et al. (2013): PLoS Med. 10:e1001403.

- Kavirajan H (2024): Am J Psychiatry. 181:342-345.

- Joralemon V (2023): Link

- Weiner S (2022): Link

- Davenport S, et al. (2023): Link

- Fibiger HC (2012): Schizophr Bull. 38:649-650.

- Insel TR, et al. (2013): Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews. 37:2438-2444.

- van Praag HM (1982): Adv Biochem Psychopharmacol. 34:259-286.

- Walinder J, et al. (1976): Arch Gen Psychiatry. 33:1384-1389.

- Papakostas GI, et al. (2012): Am J Psychiatry. 169:1267-1274.

- Bauer M, et al. (2003): Can J Psychiatry. 48:440-448.

- Newman ME, et al. (2000): Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 3:187-191.

- NIMH (2024): Link

- NIMH (2024): Link

- Kochar N, et al. (2023): Compr Psychiatry. 127:152422.

- Stein DJ, et al. (2019): Nat Rev Dis Primers. 5:52.

- Pittenger C, et al. (2014): Psychiatr Clin North Am. 37:375-391.

- Yousefzadeh F, et al. (2020): Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 35:254-262.

- Rasmussen SA (1984): Am J Psychiatry. 141:1283-1285.

- Blier P, et al. (1996): Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 11:37-44.

- CDC (2024): Link

- StopSoldierSuicide.Org (2024): Link

- Jobes DA, et al. (2019): Crisis. 40:227-230.

- Grunebaum MF, et al. (2018): Am J Psychiatry. 175:327-335.

- Lagerberg T, et al. (2022): Neuropsychopharmacology. 47:817-823.

- Cleare AJ, et al. (1995): Psychopharmacology. 118:72-81.

- Cherek DR, et al. (2001): Psychopharmacology. 157:221-227.

- Puhringer W, et al. (1976): Neurosci Lett. 2:349-354.

- Knutson B, et al. (1998): Am J Psychiatry. 155:373-379.